Charles Nicholas (pencils) & Dick Giordano (inks), The Painting, Strange Suspense Stories no.72, Oct 1964

In Roy Lichtenstein, the man who didn’t paint Benday dots, the Legion of Andy wrote about Roy L.’s assertion that there was perhaps some power in the hand of the artist capable of transforming an image from junk into art. The Legion heard this quoted by curator Sheena Wagstaff on the Tate exhibition app, listening to it (as instructed!) as we worshipped before Roy’s painting Masterpiece. What we didn’t know was the quote also appeared on the final wall of the show. This is because both times we visited we whizzed through the last rooms with their vapid “Chinese” stuff and horrible nudes and headed back out via War & Romance etc.!

On the app, this quote comes after we hear from widow Dorothy, making it very clear for us that Roy “was not a fan of comics and cartoons. It was the nature of the cartoon. It just seemed about as far away from an artistic image as you can get. To try to transform that into a formal painting with some minor changes really appealed to him.”

Here’s the quote from Roy (read by Sheena):

“It was very obvious to me that there was some underlying, difficult-to-grasp principle about art – that if two things can be very much alike to me, and one can be of great value, the other be aesthetically valueless, that there must be some very subtle thing that has to do with painting, and I was very much interested in finding out what that underlying principle is.”

Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke, 1965. Still not Ben Day dots, by the way.

We also opined that Roy was possibly taking the piss. (Isn’t that the point of his “Brushstrokes” series?) Sheena and her chums obviously don’t think he was. As she puts is: “I believe that quote is key to Lichtenstein’s endeavour… Finding out what that underlying principle is is the driving force of his work.”

The Legion says: “May the Farce be with you!”

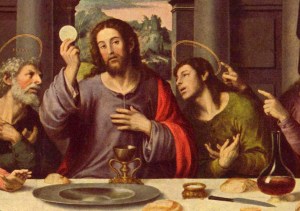

But we feel that the Lichtensteins really put their collective finger on something with these remarks about the transformative hand of the artist. The notion reminds us of the Doctrine of Transubstantiation – as in: “Roman Catholic theology… the doctrine that, in the Eucharist, the substance of the bread and the wine used in the sacrament is literally, not merely as by a sign or a figure, but in actual reality as well, changed into the substance of the Body and the Blood of Jesus.” (Thanks, Wikipedia.)

Jesus

Here it is the power of the Lord, invoked by the priest, using holy words and gestures, which transforms mundane matter into the Divine substance. In art, we are sometimes asked to believe, it is the hand of the true artist, using his/her paints and brush (or other media where applicable).

Alan Moore and David Lloyd used the idea of transubstantiation rather nicely in V for Vendetta, when the corrupt Bishop is made to swallow a poisoned wafer. The sound of the incident has been captured on tape and is being reviewed by two policemen. We quote:

This notion reminded the Legion how much people in an increasingly secular western society (let’s say at least through the twentieth century ’til now, though probably further back too) have been investing quasi-religious faith into non-religious or even anti-religious concepts. An obvious example is Spiritualism in the Victorian and Edwardian era, which sucked in the likes of Arthur Conan Doyle and H. Rider Haggard among countless other adherents.

There is an argument that the loss of religious faith (at an individual or societal level) leave a mental vacuum which attracts other beliefs, in which a similar kind of faith gets placed.

Leon Trotsky, some time ago

Here’s another favourite example of ours. Sitting in a pub in Penarth many years ago, we witnessed this exchange between friend A (a graphic /comics artist & guitarist) and friend B, the Trotskyist manager of A’s band. (Hardcore socialists must of course deny any belief in God.) The conversation had turned to B’s strongly-held political beliefs. Quoted from memory:

A (casually): The thing is, it’s become sort of a religion for you.

B (in an explosion of righteous anger): How dare you say that! You know very well I’m a dialectical materialist!

LOL, eh? Oh well. Perhaps you had to be there.

Finally we are led, of course, to G.K. Chesterton. As Wheldrake wrote: “All the branching roads in the Multiverse, as is well known, lead eventually to G.K. Chesterton. For is he not, among the literary world, the veriest Kevin Bacon thereof?”

The Sandman no. 10, 1990, by Neil Gaiman, Mike Dringenberg & Malcolm Jones III. Gilbert K. Chesterton makes his entrance (sort of).

And was it not Chesterton who said: “When people stop believing in God, they don’t believe in nothing — they believe in anything”?

Well, almost. More closely, it was Émile Cammaerts in his book The Laughing Prophet : The Seven Virtues and G. K. Chesterton (1937), and what Cammaerts actually said was: “The first effect of not believing in God is to believe in anything.” He was summing up a lengthier quote from Chesterton’s Father Brown story, The Oracle of the Dog (1923). An even fuller version of the actual Chesterton passage is quoted (slightly selectively) below by your helpful Legion. Father Brown, the priest-detective, has been told by a visitor of a dog who may have barked, by some doggy instinct, at a murderer. Father Brown is upset by this faith in the power of Dog. He says:

“It’s part of something I’ve noticed more and more in the modern world… something that’s arbitrary without being authoritative. People readily swallow the untested claims of this, that, or the other. It’s drowning all your old rationalism and scepticism, it’s coming in like a sea; and the name of it is superstition.” He stood up abruptly, his face heavy with a sort of frown, and went on talking almost as if he were alone. “It’s the first effect of not believing in God that you lose your common sense, and can’t see things as they are. Anything that anybody talks about, and says there’s a good deal in it, extends itself indefinitely like a vista in a nightmare. And a dog is an omen and a cat is a mystery and a pig is a mascot and a beetle is a scarab, calling up all the menagerie of polytheism from Egypt and old India; Dog Anubis and great green-eyed Pasht and all the holy howling Bulls of Bashan; reeling back to the bestial gods of the beginning, escaping into elephants and snakes and crocodiles; and all because you are frightened of four words: `He was made Man.'”

We are indebted to Radio 4’s Nigel Rees for the corrected attribution of this most favoured among quotations.

A God. Or possibly a Dog. Yesterday.

It is generally stated that GKC was setting his own religious faith against what he saw as the dangers of atheism. Cammaerts’s cut-down version, or an expanded “quotation” usually given as “When people stop believing in God, they don’t believe in nothing — they believe in anything” is heard all over the shop these days. Sometimes it is still a warning against the dangers of atheism, sometimes more of a wry observation of the state of things. The Legion has often used it ourselves (prefaced by “I can’t remember who said it”) but in our case as a warning against the dangers of anti-rationalism, when confronted by another claim for homeopathy, the realignment of Chakras, or whatever. It really is amazing what people will put their faith in these days.

In the case of “High Art” it seems to the Legion that just such a species of faith was at work, certainly up to the 1950s, in a middle class who took it as “Gospel” that proper art could be firmly divided from junk culture. Where the dividing line was drawn varied according to which cult one belonged to, of course. For example, anything up to a certain point in the development of Modern painting might be dismissed and abhorred as valueless rubbish – “Impressionism and Post-impressionism, oh yes, that’s proper art. But as for that Pablo Picasso… dear me no. Beyond the pale!”

Jackson Pollock, Convergence, 1952

By the end of the 1950s there was clearly a critical consensus, shared by the hipper end of the public (and probably nurtured by the CIA in their quest to sell the world American cultural power, as well as political) which invested a good deal of faith in the New York-based movement of Abstract Expressionism. Were not the likes of Pollock and Rothko channelling their artistic emotions and subconscious thingummybobs straight onto the canvas? Was this not the very essence of art, a pure distillation of the power of painting in some existentially basic form? Colour and shape freed from the tyranny of mere representation, mediated only by the transformative power of the artist himself?

This faith seems to the Legion to go hand-in-hand with belief in the Flag, Mom’s Apple Pie, Ernest Hemingway and American machismo (and quite probably the nuclear deterrent).

Another Brushstroke by Roy L.

Warhol, Lichtenstein and the US Pop movement surely challenged this whole gestalt. Is it really credible that Roy simultaneously held a belief in the transubstantiative power of the artist’s brush?