There’s a reason we don’t call it the megaverse, the pluriverse or superspace… because it’s Michael Moorcock’s multiverse.

CLICKING ON A PICTURE WILL OFTEN TAKE YOU TO A BIGGER VERSION. USE YOUR BROWSER’S BACK BUTTON TO GET BACK HERE. You knew that.

Introduction

[updated August 9th 2021 and again July 31st 2022]

If you wrote an article or made a documentary about the 1967 album Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band you would almost certainly mention the Beatles at some point — probably more than once. Likewise if you submitted a book proposal or draft podcast script about the Theory of Relativity and neglected to mention Albert Einstein, you might be asked to do a rewrite.

So why do endless articles, documentaries, podcasts and books about ‘The Multiverse’ continue to appear without any mention of Michael Moorcock, the writer who came up with the concept and gave it its name?

Moorcock wasn’t the first to use the word ‘multiverse’, as he makes clear himself, but he originated the meaning of the word as it is used today in both physics and popular fiction. The word itself is generally said to have been coined by the psychologist and philosopher William James in 1895, although as I establish in Appendix 2 below, it must have appeared significantly earlier. James and others used the word multiverse to describe our own world or universe, a single and self-contained entity, but seen from as many points of view as there are minds to perceive it — and therefore not subject to any one unique or authoritative interpretation. ‘The multiverse’ was often seen as an atheistic notion and contrasted with ‘the universe’ as ruled by a divine plan. This usage did not entirely disappear as the 20th century went on, but it remained fairly obscure.

In 1963, Moorcock either re-invented the word multiverse, or it surfaced from some forgotten corner of his memory, when he used it to name a new concept in his science fiction story The Blood Red Game. The Oxford English Dictionary acknowledges Moorcock’s novel idea, and that he originated a new meaning of the word. The dictionary defines this newly conceived multiverse as “A hypothetical space or realm of being consisting of a number of universes, of which our own universe is only one.” The OED also recognises that this meaning of the word spread from Moorcock’s science fiction to a generalised scientific understanding of the basis of reality, or ‘fact’. I will come back to this in more detail below.

Moorcock’s idea went well beyond the well-established science fiction notion of parallel worlds, to imagine the complete set of all possible worlds — as a ‘scientific’ concept and as a literary device. In a July 2021 Facebook conversation, when the issue of previous parallel world stories came up again (as it often does) Moorcock himself said this:

H.G. Wells was the first writer to discuss parallel worlds in fiction. I think he got it from Frazer. Before that people went to fairyland or another missing continent for satirical and romantic purposes [e.g. Gulliver’s travels to Brobdingnag, 1726, etc.—GL]. The multiverse connects my books and is not strictly a ‘parallel world’ or ‘alternate history’ idea, though that idea can fit into the multiverse. All parallel world stories (such as Sprague de Camp’s) are a means on which to set a version of ‘fairyland’ (science fiction version) but I wrote ABOUT the multiverse itself and, for what it’s worth, that is the simple difference.

I thought of the multiverse in terms of a visible, physical entity and theorised about its composition in conjunction with eternally recurring characters, and found a logical construct when Mandelbrot published his theories.

I used the multiverse to write what I, at least, think of as one big novel, with continuing characters carrying recurring themes and narratives, from different viewpoints and across different genres or structures of my own which I made for a particular purpose. It is on one level a device which connects all my fiction, fantastic or otherwise, enabling me and the interested reader to explore a good many ideas in some depth.

And it is worth repeating: Moorcock not only wrote about the multiverse as such for the first time, but he also gave it a name. Not a trivial detail.

It’s… everywhere.

And now the multiverse is all around us. There’s no escape from it. I don’t mean that we’re all trapped in an ensemble universe made up of an infinite number of sub-universes—though many scientists now propose that we actually are. I’m talking about the word ‘multiverse’ itself.

Surely there was a time, not long ago, when it was hardly ever heard…? And now it’s everywhere.

A case in point; the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) — currently the biggest single dollar-earning entertainment franchise on the planet — is metamorphosing into the Marvel Cinematic Multiverse.

[The usual online sources and a zillion others can be consulted as they monitor what some might describe as the ‘evolution’ or ‘development’ of Disney/Marvel’s Multiverse. Brief [updates] will appear below as they seem required. The latest one is from July 31st 2022.]

[In July 2022, the president of Marvel Studios, Kevin Feige, announced at the San Diego Comic Con that Phase 4 of the MCU, which was almost over, and the forthcoming Phases 5 and 6, would collectively be known as the Multiverse saga. (Phases 1-3 had been labelled ‘The Infinity Saga.’) Feige also showed this new logo:]

[This had been coming on for a while.] Three weeks ago [as I wrote the original version of this post], at the San Diego Comic Con (SDCC), July 2019, Feige [had] announced the title of the next Doctor Strange movie: Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, scheduled for 2021. [Eventually released in May 2022 after a change of director and extensive reworking of the story.]

Although the Marvel comics universe has been a multiverse for many years (and as I will argue below, has in fact been part of Michael Moorcock’s multiverse since 1972; see Appendix 5) Feige and his movie-making team have been playing a long game in this regard. Perhaps, as with other aspects of the Marvel Universe—including the fundamental concept of the superhero—they have felt a need to break the movie-going public in gently. Maybe it’s more about putting their own distinctive MCU stamp on these ideas. Quite likely both.

[I would now add, in 2022, that the occasionally impressive, sometimes enjoyable, often jaw-droppingly clumsy emergence of the Marvel Cinematic Multiverse has been more than a little disappointing since 2019. There are signs of a lack of coordination in overall modelling of how this particular multiverse concept ‘works’. The multiverse is also being used as the MCU’s new Big Threat, a source of nothing but danger and angst, as Thanos and the Infinity Stones were in Phases 1 to 3. I am hoping for a twist at some point, as the multiverse’s potential for wonder and positivity is also revealed. Could happen…]

[As I updated this post in August 2021, Marvels’ Loki series had recently finished streaming on Disney+, apparently setting up the multiverse as an important part of the next phase of the whole MCU. And the launch of Marvel’s new Disney+ animated series What If…? was two days away. This was named after a comic launched in 1977 to explore alternate world concepts under titles like What if Spider-Man had joined the Fantastic Four? and What if the Hulk had Bruce Banner’s Brain? In the MCU of 2021 the What If…? series became the first fruit of the post-Loki Marvel Multiverse in full swing. ]

It’s arguable that the Asgardian ‘nine worlds’ cosmology, first seen in the 2011 Thor movie, was an early example of multiversality in the MCU, but Scott Derrickson’s original Doctor Strange in 2016 was the film which explicitly introduced the term ‘multiverse’ to the MCU.

As she sent Stephen Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) on his first trip through other dimensions of reality, Tilda Swinton’s Ancient One asked him, “Who are you, in this vast multiverse?” Soon afterwards, she explained that magicians, in casting spells, “harness energy drawn from other dimensions of the multiverse.” After that the word itself was given a rest, although the main plot of Doctor Strange involved an alien dimension—another world of the multiverse—invading MCU reality. The announcement of Multiverse of Madness gave a new and unexpected prominence to the word and the concept, suggesting [pre-Loki] that Marvel are [were] keen to stake a strong cinematic claim on the multiverse.

In 2019, parallel realities, a key element of the many-worlds notion, had already been gradually creeping in. Dr Strange himself viewed 14,000,605 alternate futures in 2018’s Avengers: Infinity War. At San Diego Comic Con that year Feige also reminded us that ‘branch realities’ were explained in Avengers: Endgame (2019) during its time-travel storyline, and that the word ‘multiverse’ was heard again in its follow-up, the Sony/Marvel co-production Spider-Man: Far From Home. In Sony’s own (non-MCU) animated Spider-Man film, Into the Spider-verse (2018), alternate worlds were dramatically real; in the MCU-canonical Far From Home the super-villain Mysterio was lying about them. Nevertheless, the apparent revelation prompted an excited exclamation from teenage science-nerd Peter ‘Spider-Man’ Parker; “There’s a multiverse?!” The next entry in this series, Spider-Man: No Way Home is [was] currently scheduled for December 2021, and advance publicity teased a number of multiversal plot threads including Spider-verse-like multiple Spider-men. [Toby Maguire’s Spider-Man from Sam Raimi’s 2002-2007 trilogy and Andrew Garfield’s 2012-2014 version did indeed appear in No Way Home, establishing a form of multiversal canonicity for those non-MCU films.]

At this [that] point in Peter Parker’s fictional world, just as it is in ours, this really is [was] a word of some potency, and firmly embedded in the cultural landscape. I’m interested in how it got there.

The word multiverse may seem very new and very ‘now’ as we bandy it about today, but it has a long and—appropriately enough—multifaceted history. In this post I look at that history in some detail, but with a focus on the role of Michael Moorcock, which is so often forgotten. His phenomenally popular books of the 1960s, 70s and 80s in particular are agreed by many sources to have been the origin of the word multiverse in its current sense, yet in the media he hardly ever gets any credit for it.

Rock and role! Michael Moorcock in guitar hero days. Photo uncredited, from the Hollow Lands hb, Hart-Davis MacGibbon, 1975

Dozens of books have explored the multiverse concept, especially its emergence in science. Articles about the subject have proliferated, especially since the turn of the century, in both popular science journals and the general media. (As someone once quipped, the multiverse might not be fully embraced by scientists, but journalists love it !) But almost very time I find a new one—BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time discussion, say—I wait in vain for a mention of Moorcock.

There have been some exceptions. In Nature‘s July 2007 special issue, SF expert Gary Wolfe gave Mike some due credit.

In the world of Comics Studies, William Proctor, analysing Marvel as a transmedia quantum multiverse in editor Matt Yockey’s 2017 Make Ours Marvel says:

[T]he usage of the word as a way to describe the cosmological system of parallel worlds comes from a different source: the popular novelist Michael Moorcock.

and Andrew Friedenthal’s World Of DC Comics (2019) has a whole section on ‘Moorcock’s Multiverses’.

A notable mention in the world of science/popular science books, though not a positive one, is Dr John Gribbin’s book In search of the multiverse (2009). Gribbin says this:

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word ‘multiverse’ was first used by the American psychologist William James (the brother of novelist Henry James) in 1895. But he was interested in mysticism and religious experiences, not the nature of the physical Universe. Similarly, although the word appears in the writings of G. K. Chesterton, John Cowper Powys and Michael Moorcock, none of this has any relevance to its use in a scientific context.

My view is that Dr Gribbin has got this wrong (and not just in accepting ‘first use’ by William James — see Appendix 2, below). I will come back to this—also to the Oxford English Dictionary, James, Chesterton, and Powys.

I will also bring to the discussion a few details which I think are genuinely new, or at least largely lost to history… particularly in the Appendices at the end of this article.

And of course, this is the multiverse… if I balls it up here, at least I know there are other planes of reality where the essay ended up elegant, concise and fun to read.

Fiction and physics

The word multiverse might seem to have two distinct meanings, both of which I’m sure most readers are familiar with. It can refer to the various fictional versions which now exist—e.g. in Marvel and DC comics, games like Magic: The Gathering, and many more. The web site TV Tropes has a long list of these which might or might not be exhaustive, and includes a brief section called ‘Real Life’. This, of course, acknowledges the second meaning of the word; a multiverse that modern physics suggests might be the actual structure of reality. However, like two particles with quantum entanglement, these two categories of multiverse are bound up with each other in an intimately shared history.

I’m proposing that the word multiverse was originally used in this way in fiction—specifically Moorcock’s science fiction and fantasy from 1963 onwards—then migrated not only into other fictional multiverses, but also into the world of physics.

Admittedly, the multiverse might seem to have arrived in physics first, and this is an aspect which I need to deal with. Here, the multiverse concept is often dated to 1956, when Hugh Everett III wrote his original (and highly controversial) PhD thesis on quantum mechanics; or 1957, when a shortened version of the thesis was finally accepted and published. Both versions of the thesis can be read in this 2012 book by Peter Byrne and Jeffrey A. Barrett.

Challenging the accepted quantum science of the time, Everett introduced what Barrett & Byrne call “the strange, brilliant, revolutionary idea widely known as the ‘many worlds’ interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics.” Notably though, Everett didn’t use the word multiverse. In fact, as Barrett & Byrne have to admit, “Everett himself never mentioned many worlds or parallel universes in either version of his thesis.” His theorizing required further clarification, notably by Bryce S. DeWitt, who gave it the ‘many worlds’ name in 1970, and whose “interpretation of Everett so captured people’s imagination that it remains the most popular understanding of Everett’s theory.”

The first indication that quantum physics might imply a number of different realities in fact goes back to 1952, and a lecture given by physicist Erwin Schrödinger.

In 1935 he had proposed his famous thought experiment involving a cat in a sealed box, whose fate depended on whether a single atom underwent radioactive decay or not. Quantum mechanics said that the atomic event was only a matter of probability until it was observed, at which point the “wave form collapsed” one way or the other, and it became a yes or a no. Schrödinger didn’t accept this, and his cat scenario was actually a joke, pointing out the absurdity of the claim by scaling it up. The cat was neither dead nor alive, or else it was both dead and alive, until an observer opened the box, when it settled into one state or the other.

According to the MWI, the cat is alive in one universe and dead in another. In 1952 Schrödinger (sort of) suggested much the same thing, but he didn’t re-use his cat analogy. If he had, his assertion made have made more impact. As it was (in our universe anyway) it seems to have gone no further than the lecture hall at the time. It may just possibly have influenced Everett’s own thinking, though. I’m grateful to John Gribbin, whose In Search of the Multiverse includes this little-known twist in the cat’s tale; also to Wikipedia for the illustration below, using Schrödinger’s cat to illustrate the MWI.

In 1973, DeWitt and Neill Graham published the book The Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, collecting all the currently available scientific literature on the subject.

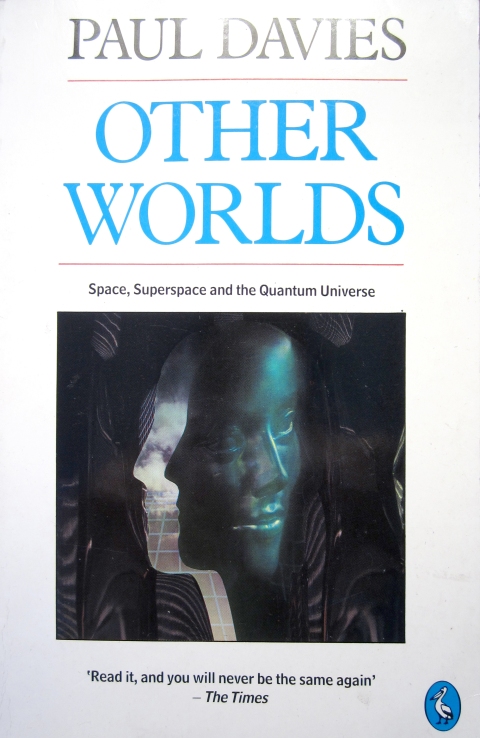

By 1980, ‘many worlds’ remained the name associated with the Everett/DeWitt interpretation. In that year, Paul Davies, a professor of theoretical physics, published his book Other Worlds, discussing the concept in detail. Davies did not use the term multiverse. He wrote of alternate worlds and parallel universes, saying: “If we now picture all the possible worlds […] as a sort of gigantic, multi-dimensional super-world…” The word he settled on most often for this structure was ‘superspace’.

Clearly the world of physics was crying out for the word multiverse. If only more of these people had been reading Michael Moorcock. Or… perhaps some of them were…

The 1997 book The Fabric Of Reality by David Deutsch, a pioneer of quantum computing, was one of the first to set the multiverse firmly in place as a completely serious scientific notion. (The Marvel movie Avengers: Endgame explicitly uses Deutsch’s limitation on time travel, as described in this book—i.e., any changes you make in a past time cannot possibly affect the time (reality) that you came from (and might hope to return to). Instead any such change produces a new branch reality. Another very Moorcockian concept, as it happens.)

And with this book, the word multiverse itself had very much arrived. I quote just one of many, many mentions:

Most physicists prefer to carry on using the word ‘universe’ to denote the same entity that it has always denoted, even though that entity now turns out to be only a small part of physical reality. A new word, multiverse, has been coined to denote physical reality as a whole.

David Deutsch did not mention Moorcock in his account, but as I will show below, he accepts that the word multiverse very probably arrived in the world of physics from Moorcock’s books. Deutsch dates this as far back as the 1970s, even though it didn’t make it into Paul Davies’s book in 1980 (or its 1988 paperback edition).

Deutsch’s own multiverse was very much of the quantum physics variety, accepting the Everett-DeWitt Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI) and moving on from there. But, as science-historian Helge Kragh showed in his 2009 survey of the field, a number of new multiple-universe theories emerged from other areas of science in the 1980s and 90s. Since his article is not widely available, I have pulled out a number of quotes below. This includes Kragh’s single brief mention of the MWI, perhaps implying that it was no longer any kind of front-runner in the multiverse-theory sweepstakes by 2009.

The inflation theory of the very early universe did much to change the situation, especially in the versions of ‘chaotic’ and ‘eternal’ inflation introduced by the Russian physicists Andrei Linde and Alexander Vilenkin in the early 1980s. […]

According to the self-reproducing or eternal inflationary scenario, pocket or bubble universes will be produced constantly from regions of false vacuum and the universe (or multiverse) as a whole will regenerate eternally. Vilenkin claims that [this] makes the multiverse ‘essentially inevitable’, a claim supported by other multiverse enthusiasts.[…]

By 1990 there existed a variety of ideas of how multiple universes might be generated. Some of them were based on inflation theory, others on hypotheses of cyclic universes, and others again on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. […]

Since the beginning of the new century there has been a marked change in the interest for and attitude to the multiverse, with many eminent physicists having ‘converted’ from the idea of a single universe to the possibility of many universes. Part of the reason has been […] the discovery in 1998 of the accelerated expansion of the visible universe. Another important reason, apart from the inflation theory, is that advances in string theory (or M theory) have inspired confidence in the multiverse.

Andrei Linde himself describes the 1998 watershed moment thusly:

The situation changed dramatically only after the discovery of the cosmological constant/dark energy and the development of the string theory landscape [the calculation that there are 10500 universes in the multiverse; more than there are atoms in our universe].

Here I will leave the science of the multiverse, at least for now. Wikipedia has a current summary of this still-evolving field—one which, I’m pleased to find, credits Michael Moorcock with the first use of the term “in fiction and in its current Physics context”.

Two final points though: firstly, there has been and remains a degree of scientific doubt whether any of the various multiverse scenarios is likely to be ‘real’—or at least, can ever be scientifically proven one way or the other. As proposed by Popper, if there is no way to prove an idea false by experiment, it’s not science, but pseudo-science; not physics, but metaphysics. Everett’s ‘many worlds’ were by definition closed to us (though Deutsch interprets experimental ‘interference’ effects as actual evidence). Other types of multiverse may or may not leave traces in our universe. Paul Davies, of Other Worlds and ‘superspace’, perhaps surprisingly, wrote a famous and famously sceptical piece in the New York Times in 2003. Among other things he said:

The fashionable scientific response […is…] the so-called multiverse theory. The idea here is that what we have hitherto been calling ”the universe” is nothing of the sort. It is but a small component within a vast assemblage of other universes that together make up a ”multiverse.” […]

How seriously can we take this explanation […]? Not very, I think. For a start, how is the existence of the other universes to be tested? […] As one slips down that slope, more and more must be accepted on faith, and less and less is open to scientific verification.

Extreme multiverse explanations are therefore reminiscent of theological discussions. Indeed, invoking an infinity of unseen universes to explain the unusual features of the one we do see is just as ad hoc as invoking an unseen Creator. The multiverse theory may be dressed up in scientific language, but in essence it requires the same leap of faith. […] To a scientist, it is just as unsatisfying as simply declaring, ”God made it that way!”

Davies, BTW, was possibly the first to use the Hawking-derived title ‘A Brief History of the Multiverse’ for that article—or perhaps it was an inspired NYT sub-editor—but he certainly hasn’t been the last. I thought I’d been very clever and invented the title when I first planned this post. I soon found out differently. Not entirely dissimilar to Michael Moorcock’s use of the word multiverse itself, perhaps? As above, so below…

Secondly: writers like Helge Kragh and Andrei Linde (who both used ‘A Brief History…’!) discuss multiverse theories with admirable historical and scientific rigour, but without bringing any rigour to the question of its naming; not even to the basic question, ‘Just when did ‘many-worlds’ become ‘multiverse’ in the world of science?’

For example, in his 1982 paper Nonsingular regenerating inflationary universe, Linde wrote:

In the scenario suggested above the universe contains an infinite number of mini-universes (bubbles) of different sizes […]

And his 1987 paper Particle Physics and Inflationary Cosmology was still introduced like this:

It seems likely that the universe is an eternal, self‐reproducing entity divided into many mini‐universes, with low‐energy physics and perhaps even dimensionality differing from one to the other.

It ‘seems likely’ to me that Linde would have used the word multiverse here, if it was then current in his scientific context. However he might have used it in the body of the paper itself, which I can’t read online… and this underlines the difficulty of trying to answer the question of when and how the multiverse got its name in science.

By 2012, Linde was definitely using the word, as seen below.

Finally, in 2009 Helge Kragh said this:

In this paper I shall [consider] the class of cosmological theories which postulate the existence of many universes, often referred to as the multiverse. (Other names appear in the [scientific] literature, such as ‘megaverse’, ‘pluriverse’, and ‘parallel universes’.)

Fair enough, but there has to be a reason none of those other names was being widely used in 2009, and nor was ‘gigantic, multi-dimensional super-world’. That reason, I contend, was Michael Moorcock. Let’s see if the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) agrees.

The multiverse in the OED

When writing about the meaning or history of a word, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is certainly a traditional place to start. When I looked at its entry on ‘multiverse’, I was pleased to find that the OED did indeed agree with me on the Moorcock connection. (Is that a point for me or a point for the OED? :0)

On ‘multiverse’, noun, the OED lists three meanings, 1.a., 1.b. and 2..

Meaning 1.a. is where William James and John Cowper Powys come in; I’ll get to that a bit later.

Meaning 1.b., which is more recent, is the one which is most relevant to our current usage. The OED says this:

1.b. originally Science Fiction. A hypothetical space or realm of being consisting of a number of universes, of which our own universe is only one; (Physics) the large collection of universes in the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, according to which every event at the quantum level gives rise to a number of parallel universes in which each in turn of the different possible outcomes occurs.

It then goes on to quote a number of sources or examples of this usage, starting with what its compilers think is the earliest:

1963 M. Moorcock in Sci. Fiction Adventures vol. 6, no. 32. Jewelled, the multiverse spread around him, awash with life, rich with pulsating energy.

1982 Time (Nexis) 15 Mar. 92 The task of the science-fiction writer, said [Philip K.] Dick, ‘is creating multiverses, rather than a universe.’

1990 New Scientist 9 June 37/2 The wormhole picture changes our view of the ‘origin’ of the Universe in a big bang, which is now seen simply as the event corresponding to our Universe branching off from the greater ‘multiverse’, to which we must still be connected by an umbilical wormhole.

1994 Interzone Sept. 27/2 Suddenly there was insight. He could treat it as a single object existing simultaneously at all levels in a multiverse.

1997 M. Rees Before Beginning 3 What’s conventionally called ‘the universe’ could be just one member of an ensemble. Countless other universes may exist… This line of thought—the enlarged perspective of the ‘multiverse’—supplies a motive for this book.

2000 Nature20 Jan. 247/3: Twenty years ago the Multiverse concept would have seemed utterly far-fetched, but now it threatens to become conventional wisdom.

There is so much to be taken from this entry alone, and some of it might have to wait for future discussion. For now, three things immediately appear to demand attention:

First, the OED defines the ‘science fiction’ and ‘science fact’ meanings of the word together. This seems surprising—shocking, even! Surely we’d expect the two to be separated out…? Is the OED implying that Moorcock’s creation of the fictional multiverse in some way led to physicists taking another look at the factual universe, and finding in it newly evident, previously hidden layers of reality?

Well, no, it isn’t, of course; the OED’s interest, even more tightly than mine, is focussed on the word. What the dictionary is implying, which might at first seem almost as surprising, is that the word multiverse started in science fiction and spread from there to the world of science fact. That, of course, is an assertion I am completely comfortable with.

(I do speculate, however, that the two meanings might become separated in a future edition of the OED. This entry for ‘multiverse’ dates back to 2003, and it has been updated twice, having appeared originally in the 1933 Supplement, and getting updated for the 1989 edition. It would be a shame if the very close links between the SF and scientific meanings became lost or watered down in future.)

(Also, while I’m in parentheses, the 2003 date explains, I think, why the ‘physics’ meaning as defined here is confined to the field of quantum mechanics and the MWI. I imagine that the OED has already been alerted to the newer manifestations of the multiverse in the scientific realm.)

Secondly, there is a gap of 27 years between the first appearance of meaning 1.b. in a 1963 science fiction story, and the first quoted passage from a factual science magazine in 1990—albeit ‘multiverse’ appeared in New Scientist in ‘scare quotes’. This at least pushes the date of the fiction-to-physics migration back from 1997 by seven years, and David Deutsch’s book which I quoted above (and Martin Rees’s, mentioned here in the OED, which I’ve yet to read). Did it really take that long for the word multiverse to make the transition? Well, David Deutsch says not… again, more on this later.

Moorcock, of course, is the third Interesting Thing to leap out of OED: multiverse 1.b., which makes it clear that the origin of the word as we use it today is seen by the dictionary to lie in his writing. That is, in both the fiction and the physics—from the Marvel universe to the learned journals—the OED concurs that Michael Moorcock coined the term that is now more widely used than any other for Paul Davies’s ‘gigantic, multi-dimensional super-world.’

James, Chesterton, Powys & co.

The OED’s meaning 1.a. of multiverse is “The universe considered as lacking order or a single ruling and guiding power.” The earliest known quote using this meaning is given as:

1895 W. James in the International Journal of Ethics: “Visible nature is all plasticity and indifference, a multiverse, as one might call it, and not a universe.”

(I have found an earlier published example of this meaning; see Appendix 2 at the end.)

William James (1842-1910) was an influential American psychologist and philosopher. He was a pluralist, taking the philosophical position that rather than one consistent means of approaching truths about the world, there were many—as opposed to monism, which stresses the unity of all things. He was a co-founder of the philosophy of pragmatism, which Wikipedia tells me contends that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, meaning, belief, and science—are best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes, and focussing on a changing universe rather than an unchanging one.

James was not referring to other worlds, but characterising our own world as one in which many different points of view exist, and are often in conflict. The quote is from a talk called ‘Is Life Worth Living?’, given to the Harvard Young Men’s Christian Association. Specifically, in this passage, James was talking about the idea that nature itself might be worthy of religious reverence, and rejecting it. His audience may well have understood this to be a critique of pantheistic ideas attributed to Jean-Jaques Rousseau. To extend the OED’s quote a little:

Truly, all we know of good and duty proceeds from nature; but none the less so all we know of evil. Visible nature is all plasticity and indifference,—a moral multiverse, as one might call it, and not a moral universe. To such a harlot we owe no allegiance; with her as a whole we can establish no moral communion; […] If there be a divine Spirit of the universe, nature, such as we know her, cannot possibly be its ultimate word to man.

The OED’s quote, as you may have noticed, does not have the word ‘moral’; I’m not clear if this was in the original lecture or added to the published version for clarification. Sometimes the quote is given with brackets, like this: ‘a (moral) multiverse, as one might call it, and not a (moral) universe.’

Later, in his book A Pluralistic Universe (1909), while still rejecting monism, James was to write:

We still have a coherent world, and not an incarnate incoherence, as is charged by so many absolutists. Our ‘multiverse’ still makes a ‘universe’; for every part, though it may not be in actual or immediate connexion, is nevertheless in some possible or mediated connexion, with every other part however remote, through the fact that each part hangs together with its very next neighbors in inextricable interfusion.

James’s use of ‘multiverse’ seems to have been quite influential, especially amongst Christian churchmen, who clearly associated it with atheism. This aspect of the word and its history has emerged from my own research. Despite the intellectual climate of the 1890s, which was highly conducive to atheism, James—like Galileo and Charles Darwin—did not explicitly reject the idea of God (in his writing, at least). Indeed, he was intrigued by religious experience and wrote about it at length. It seems clear though that the notions of pragmatism, pluralism and the Jamesian multiverse itself were potentially tools in the atheist toolbox—arguably not compatible with any monotheistic deity and his authoritative plan for the human race.

Throughout the twentieth century, I have found, Christians could be heard proclaiming that “We live in a Universe, not a Multiverse”. As my searches through old books and newspapers have shown, this became something of a catchphrase of theirs. The most recent example seems to be from 1999, in volume 3 of R.J. Rushdoony’s The Institutes of Biblical Law:

The presupposition of the university is Christian in that it is assumed that, because there is one God, there is a common universe of truth, law, and meaning. If, however, we have a multiverse, many systems separately evolving out of nothing, there is no common origin and meaning.

The implications of this, while seldom stated explicitly are revolutionary. Without the Biblical God, there is no common meaning, and truth is as diverse as the multiverse.

Let’s be clear; Rushdoony does not think this is a good thing.

The British author G.K. Chesterton (1874 – 1936) occasionally referred to the multiverse in a similar way. That isn’t him below; that’s John Cowper Powys.

Powys is the other writer with whom the word multiverse is often associated, including in ‘OED 1.a.’:

1957 Times Lit. Suppl. 11 Oct. 602/1: It is precisely Mr Powys’s ever-present contact with the vital, or spiritual, principles within the universe which enables him to explore… the deeper problems of that comparatively small section of the universe—or as he would say multiverse—which constitutes man.

Powys was an Englishman who in later life rediscovered his Welsh roots. In his 1942 non-fiction book Mortal Strife, he explicitly adopted the William James meaning:

I keep repeating William James’s strange word ‘Multiverse’ because I feel that it is infinitely satisfactory to hold in our mind that the world we live in is not—to use another expression of William James—a ‘block-universe’ [James’s conception of the universe as seen by monism].

And later in the same book:

What wonderful, what startling possibilities are suggested by William James’s pluralistic system of things or ‘multiverse’!

In later writings, Powys’s use of the word took on a more mystical tinge, in keeping with the author’s developing spirituality, which—paradoxically, given James’s original intention—came very close to nature-worship. Powys’s multiverse became loosely associated with other worlds which he believed that the human soul, if not the mind, was in touch with. Powys did not however attempt to construct a ‘many worlds’ cosmology, though I have found this intriguing passage from his 1953 book In Spite Of: a Philosophy for Everyman:

I refer to the staggering mathematical hypothesis of a number of dimensions other than the one with which we are familiar. This is indeed a stroke for the mental liberation of individual man and woman that cannot be over-praised. But the problem for us is how an individual soul can accept what surrounds it in the enormity of such a multiverse without going mad.

Just which ‘mathematical hypothesis’ Powys was referring to here remains, for now, just one more mystery of the multiverse. If any reader can shed some light on this… please do!

Finally, OED meaning 2…

2. figurative. A sphere of very varied possibility, such as the mind or the imagination.

1987 N. Spinrad Little Heroes 96 How many times had she experienced such a magic moment of reality transformation from on high as the LSD or the mescaline or the peyote began its rush through her brain, as ordinary earth-bound reality dissolved into the multiverse of the infinite possible, taking her spirit with it?

1993 Sci. Fiction Stud. Nov. 457 Postmodernist fiction… assumes that the world is not one, that we function in an ontologically plural multiverse of experience in which the classical subject is decentered and fragmented.

Hmm… isn’t this something of a mash-up of 1.a. and 1.b.? Perhaps that’s just a reflection of how words get new meanings. Anyway, keeping this brief; Spinrad — good to see another author of literate SF in the OED… Bug Jack Barron! Last Hurrah of the Golden Horde… tasty!

And let’s not even get started on quantum physics, the multiverse, postmodernism, post-structuralism, post-truthiness, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Delueze, the rhizome etc.. That is another whole blog post, if not several, and that is someone else’s job. Reader… you write it. (And send me the link.)

Meanwhile, back at Michael Moorcock…

You can read far more about him at the above link than I can fit in here. Recipient of the 2008 Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Grand Master Award; born 1939; in 1957, teen prodigy editor of UK comic Tarzan Adventures; journalist and comics scripter, SF and fantasy author who hit big with the Elric of Melniboné stories in the magazine Science Fantasy, starting in 1961…

His novella in Science Fantasy‘s companion title Science Fiction Adventures no.32 (May 1963), quoted in OED:1.b., was called The Blood Red Game; the sequel to The Sundered Worlds in no. 29 (Nov 1962). The two novellas have subsequently been published together several times under one or other name (generally to some extent rewritten).

The original story, in its early pages, appears to be a homage to, or a late entry in, a genre established partly by Edgar Rice Burroughs and developed by US pulp magazine Planet Stories (1939-1955). Especially as written by Leigh Brackett, these yarns are often called ‘planetary romances’ or themselves simply ‘planet stories’. However, The Sundered Worlds enters new territory with the appearance near the edge of ‘our’ galaxy of an alien solar system, found to follow its own orbit through multiple universes, and establishing Moorcock’s fictional multiverse for the first time. The word itself did indeed first appear in his oeuvre, as the OED says, in the original publication of The Blood Red Game.

Moorcock went on to develop the idea in depth, sometimes in more serious fiction, but most notably, in terms of massive sales figures—the reason so many impressionable young minds would have been exposed to the idea of the multiverse—in his fantasy novels of the 1960s and 70s. Mass-market paperbacks of his popular series sold in their tens of thousands, were reprinted and collected and box-setted—often re-titled and re-issued—throughout the English-speaking world and in translation. This continued into the 1980s and beyond, and most of his titles are still in print today.

His latest book, The Whispering Swarm, (2015), his closest yet to autobiography, still finds another new way of looking at the multiverse. It’s also a meditation, in particular, on the writer’s conflicting impulses towards escapism and political engagement.

Many of Moorcock’s earlier characters, like Elric, Prince Corum, Dorian Hawkmoon and Jerry Cornelius, were reincarnations of one being, The Eternal Champion. He, occasionally she, was doomed to take sides in the never-ending struggle between the forces of Law and Chaos, the conflict which largely displaced the more simplistic notion of Good vs. Evil in Moorcock’s fiction. The various Champions lived in different worlds within Moorcock’s multiverse; one huge—possibly infinite—series of parallel universes, ‘planes of reality’ sometimes well known to each other and accessible by means of magic or science, sometimes less so.

This is not to imply that Moorcock invented the idea of ‘parallel’ or ‘alternate’ worlds, which of course was already long-established in fantastic fiction. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction traces it back to 1895, in stories by H.G. Wells and Joseph-Henri Boëx. There is no doubt that Moorcock did something radically new with the concept when he developed his multiverse—websites like Wikipedia and the Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction in addition to the OED, credit Moorcock with this game-changing creation.

Whether Moorcock picked up the word itself from a book by Powys, or it came to him de novo, is lost to time and memory. For the first issue of his DC/Helix Multiverse comic in 1997 he wrote:

Whether I or the great Welsh poet and philosophical novelist John Cowper Powys invented ‘the multiverse’ some thirty-five years ago isn’t particularly important, since Powys’s mighty romantic mind had much more elevated discursive and philosophical uses for the concept.

I developed the idea from lowlier origins—from Rider Haggard and Robert E. Howard—in an effort to bring what I hoped was increased sophistication, subtler metaphor, to science fantasy storytelling.

Moorcock kept an eye on scientific advances, incorporating ideas from string theory (as well as role-playing games) into later multiverse stories. Also in 1997, in a piece for the book Tales from the Texas Woods, he wrote:

Since the advent of Mandelbrot’s extraordinary observations, the creation of Chaos Theory and Chaos Mathematics, I have been able to give further coherence to my notion, by suggesting we perceive each fresh ‘plane’ of the multiverse as a ‘scale’—that scale alone differentiates them when so close together. The greater the variance of scale, the greater the variance of history and personal lives.

My own interest in the multiverse has always been more in the narrative device than the real or supposed science — though the beautiful, infinitely repeating images of Mandelbrot sets are admittedly a delightful adjunct to the Moorcockian vision. Still, whether reality might actually have a multiversal structure or not seems very remote from most people’s lives, even if quantum computers, bringing us even faster computing power, seem to work partly in other dimensions. Moorcock’s genuine innovation was to bring together a wide-ranging body of work under the umbrella title. Within the storyworld—intradiegetically—characters may (or may not) understand that they live in this multiverse, and the concept can also inject extra dramatic elements, for example various levels of difficulty crossing from one world to another when the need arises.

Outside the stories, extradiegetically, the overarching structure reflects a certain thematic unity across the many strands of Moorcock’s fiction. Perhaps it gave readers an added level of investment in Moorcock’s oeuvre, transforming some into fans with a mission to ‘collect the set’. (Hello, thirteen-year-old me! It’s a good thing I was much too old for Pokémon.) Moorcock wrote a lot of more ambitious, serious material—including a good deal of non-fiction—alongside his lighter fantasy and SF, and financially supported the ground-breaking magazine New Worlds, where others could do the same. The multiverse notion may have helped to carry some fantasy readers towards more earnest fare, though it should be stressed that even the ‘lightest’ of Moorcock’s fantasies were not written cynically, and they often embody his anti-authoritarian politics.

Plus, they are far, far better than most of the crummy rip-offs that followed, in a post-early-Moorcock (and post-Tolkien) world where publishers were very keen to get fantasy books on shelves. This is not to damn Moorcock with faint praise. I frequently re-read segments of the Eternal Champion saga to this day, and always with great pleasure.

Moorcock’s success bred both flattery and of course, imitation; the latter on a massive scale. The struggle between Law and Chaos was ‘hommaged’, borrowed, stolen and occasionally even licenced by any number of other writers and, especially, role-playing games companies.

The eight-arrowed Chaos symbol in particular, Moorcock’s creation, cropped up all over the place—long before the internet made such viral spreading even easier. The multiverse concept too proliferated within the hugely widespread field of gaming.

Summing Up

From Moorcock’s massive achievement in popular culture, then, I believe that three linked but separable phenomena flowed:

Firstly, the idea of a multiverse tying together linked series of games, comics and books became increasingly common, and gradually spread into TV and movies. As outlined above, this has almost certainly been both a genuinely well-liked trope—by creators, readers, players etc.—and, in many cases, something of a marketing ploy.

Secondly, the name multiverse has stuck pretty firmly to most of these new examples. No doubt there is at least one universe, somewhere out there, in which Moorcock trademarked both the Chaos symbol and the Multiverse. On that plane of existence he lives in unbridled luxury, simultaneously funding several good causes. Unfortunately, that reality isn’t the one we’re living in. Of course, there is also at least one world where he trademarked both, but where all the rip-off Chaos symbols have six arrows, not eight, and there are lots and lots of ‘Megaverses’. On those planes, only the lawyers are making big money.

Thirdly, the name multiverse escaped from fiction into science. While many of Moorcock’s hundreds of thousands of readers in the 60s, 70s and 80s were simply digging Moorcock’s brand of ‘science fantasy’ escapism, a good proportion of them will have had some real interest in the sciences. The timing seems right for Moorcock’s original multiverse to have been the one which inspired one or more scientists to adopt the word.

I put this notion to Professor David Deutsch, aforementioned quantum champion, in 2014, when I started looking into the topic—and before I’d seen the OED entry. Wikipedia, in an earlier (and no longer current, even in 2014) article had reported that Deutsch had read some Moorcock, and therein found the word multiverse. I found this unlikely, as he didn’t mention Moorcock in The Fabric Of Reality, and I said as much in an email.

“No I hadn’t read it at that time,” he replied.

I also wrote: “Moorcock’s books were enormously successful in the 60s & 70s, and it strikes me that many young scientists or scientists-to-be would have read them. I wonder then whether the term may have originated in his fiction, and percolated into scientific circles.”

Prof Deutsch replied “I think that’s likely.”

He went on to write this neat summary:

I’m far from being an expert on the history of this term, but as far as I know, it happened like this:

First, the term was used by arty or philosophical people to mean the universe considered as a disorganised thing, not unified by underlying principles. This usage is obsolete, though I see that the OED has an example from as recently as 1985 [Oliver Sacks, The man who mistook his wife for a hat].

Second, Michael Moorcock used it in the 1960s to mean a collection of universes. I was unaware of this.

Third, it came into informal use by physicists referring to the Everett interpretation of quantum theory.

Fourth, I used it, starting in the late 70s, conforming to that existing, informal usage. (I didn’t think I was coining anything.)

Fifth, suddenly, people started using it in regard to the fine-tuning problem, and then in regard to string theory. I thought that that was regrettable and would cause confusion.

So, as I mentioned above, Prof Deutsch adds to our previous knowledge that Everett/MWI proponents were using the word multiverse by (or before) the late 1970s. This again pushes back the date well beyond New Scientist’s first recorded mention (according to the OED) of 1990.

So… next time you read an article, listen to a podcast, watch a documentary about ‘the’ multiverse, or any specific multiverse in particular, and Michael Moorcock doesn’t get any credit, please feel free to complain politely to the makers. Send them the link to this post; it might save you some time.

Clearly, though, once a word accumulates the kind of weight and reach that ‘multiverse’ has—its own payload of cultural capital—it will be used by people who genuinely don’t know that it originated with Moorcock. Many will believe that it was invented in the world of physics. We must not come down hard on these poor benighted souls, like some agents of Chaos. Gentle nudges in the right direction must be the Order of the day.

Or at the very least, grumble, swear a bit or SHOUT! at that magazine, TV, radio, laptop, iPad, phone or other communications device of choice. That’s what I’ve been doing for years. It’s working out well so far.

Appendices

There are a few things which haven’t found their way into the main body of this text, but I think deserve an airing. There are a few new finds here—some more meaningful, or more serious, than others.

- New Scientist Magazine

- An earlier appearance of the word multiverse

- An earlier SF multiverse

- An etymological quantum multiverse from 1960

- Moorcock’s Multiverse invades the Marvel Universe

Appendix 1.: New Scientist magazine

Since the New Scientist archive is now searchable from 1956 to 1989 on Google Books, I can tell you that a search for ‘multiverse’ therein finds only one mention, from 1976—not actually in a scientific sense, but in a review of an exhibition of Islamic science and technology. And though the word was attributed to Robert Oppenheimer, so-called ‘father of the atomic bomb’, his usage—as explained here—was most definitely William James’s. Oppenheimer used the word while giving the William James lectures at Harvard University, quoting James himself, and expressing the hope that science would sort out the disorganised multiverse, or ‘cognitive jungle’, of knowledge which Oppenheimer deplored in his contemporary world.

Hugh Everett III also got a single mention during these years. His original 1957 publication was given a New Scientist review in January 1958, but the ‘many worlds’ implication (always somewhat under-emphasised by Everett) doesn’t get a mention here.

The Many Worlds Interpretation got four mentions, all between 1984 and 1987—none using the word multiverse. In a December 1984 review of John Gribbin’s book In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat, the MWI was dismissed as a ‘dissident viewpoint’ and ‘metaphysical’. In March 1985 Gribbin wrote a page in favour of this “minority view”. “Science-fiction writers (and readers) love it. Most physicists abhor it […]” he noted. In September 1987, the MWI was mentioned in passing in another book review. Yale physics professor Lee Smolin’s October 1985 article ‘What is quantum mechanics really about?” said this about the MWI:

I will not attempt to convince the reader that this is reasonable, or unreasonable. Some physicists find it extremely appealing, whereas others have difficulty understanding how anyone can take it seriously. At a recent meeting in Oxford, physicists interested in quantum gravity voted on the issue, and the result was about even, for and against.

Appendix 2.: An earlier appearance of the word multiverse than 1895

On the correspondence page of Scientific American magazine, Nov 22, 1873, a letter appeared from William Denovan, scientist and author of popular science books. At some length, he argued that a previous correspondent had got it wrong about planetary motion. Denovan’s science is very convoluted and very 19th century and need not concern us here; anyway, it’s not the science of multiple worlds that he’s discussing. What’s interesting is how he signs off:

I must record my conviction that Science never can advance to a generalization of all the forces of Nature until it recognizes the fact that the substratum of mechanical power, appertaining to every unit, is as infinite and eternal as space and time in the will of God—that the Great Mechanic presides over a universe, and not merely a cohering multiverse.

Here, some 22 years before William James’s famous 1895 example, is the word multiverse… and not even in ‘scare quotes’.

The meaning is much the same as James’s, but with that Christian emphasis which I noted above—‘it’s God’s universe not a godless multiverse’. (Another scientist who believed that “God doesn’t play dice”!)

The OED has been informed.

Appendix 3: an earlier Science Fiction multiverse

Before there was science fiction, as a named category, there were ‘scientific romances.’ The Triuneverse: A Scientific Romance, by R.A. Kennedy, a self-proclaimed “metaphysician”, was published in London in 1912. As a fictional narrative, the book is perhaps best described as ‘bonkers’. Nature reviewed it; this is the entire review:

One gets rather tired of these ” Looking Backward” books, which usually follow Mr. H. G. Wells, longo intervallo [from a great distance]. The one under review begins at 1950 A.D., and opens with a description of some astronomers watching Mars split into two, then into four, and finally into about 500 bits. This cluster then proceeds to swallow Jupiter and Saturn; the sun blows up, and the earth starts off somewhere on a wild career, with a piece of sun just big enough to keep it fairly warm. Then two of our astronomers suffer a magical shrinkage in size, entering the infra-tonic (less than electronic) world. And here we may as well leave them, for Nature is a scientific journal, and this book, though a romance of science, is more of the former than the latter.

The book isn’t exactly a secret, having picked up brief mentions in SF commentaries. For example, The Encyclopedia of SF has it in its Great and Small section:

The idea that there might be worlds within worlds was popularized by the Rutherford-Bohr model of the atom as a tiny “solar system” with electrons orbiting the nucleus. The notion that all the atoms of our Universe might be solar systems in their own right, and all of our Universe’s solar systems themselves atoms in a macrocosm, was developed by several writers, appearing first in The Triuneverse (1912) by R A Kennedy.

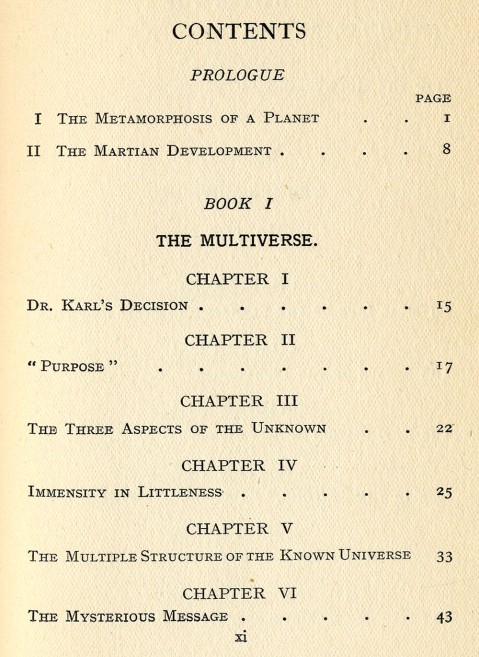

What has escaped attention, or perhaps escaped comment because of reasons, is the multiverse angle. The first pages of its extensive contents listing is shown below:

‘The multiple structure of the known universe’ in Chapter 5 is as outlined in the Encyclopedia; every atom of our universe is a tiny solar system (and its own particles, electrons, are made of even tinier ones, infratons, etc.); in turn, our solar system is an atom in a larger structure, etc. Much of this was taken straight from a 1907 book, which Kennedy plugged at the end, the supposedly serious and scientific Two New Worlds, by E. E. Fournier d’Albe. Here the tiny solar systems constitute the Infra-world, and the big stuff is the Supra-world, and at one point:

In the accompanying diagram a multi-universe is shown […] . Though this is not the plan of the infra-world or the supra-world, the diagram is useful in showing that an infinite series of similar successive universes may exist without producing a ‘blazing sky’.

The diagram, which sounds so exciting, is actually very dull. Well, this is proper science, not some coffee-table effort.

This structure clearly gave Kennedy the name ‘The Multiverse’ for his physical universe. However, he doesn’t stop there; the presence of life makes the Multiverse into an Organiverse, which due to the presence of Spirit within living things makes it into a Spirituverse. Somehow the whole thing is a Triuneverse, and God comes into it somewhere. The book’s crazed ‘plot’ is just a frame to hang all this ‘metaphysical’ stuff on. Perhaps Kennedy had aspirations to found a cult. After writing this book he seems to have disappeared from historical view. Any sightings gratefully received.

It’s tempting to construct an argument that The Triuneverse is a neglected masterpiece which must have inspired Powys, brilliantly anticipates Moorcock and Mandlebrot, etc., but life is too short, and word count too long, for satire. Equally, while it is undoubtedly an exemplar of its time, when the Edwardian public were being fed all sorts of pseudoscientific and spiritualistic mumbo-jumbo… no time for serious sociocultural analysis either.

I very much doubt if this book really fits into our narrative anywhere. It’s unreadable, but as a curio, clearly belongs on the shelf of any collector with even a passing interest in the multiverse.

Appendix 4: An etymological quantum multiverse from 1960

In John Gribbin’s book, In Search Of the Multiverse, he says that the word multiverse became associated with the 1956 Everett interpretation of quantum physics as early as 1960, some two years before Michael Moorcock wrote The Blood Red Game, and ten years before DeWitt named the ‘Many Worlds Interpretation.’ In December of 1960, A Scottish amateur astronomer called Andy Nimmo…

was the Vice-Chairman of the Scottish branch of the British Interplanetary Society, and was preparing a talk for the branch about a relatively new version of quantum theory, which had been developed by the American Hugh Everett.

[…]

But Nimmo objected to the idea of many universes on etymological grounds. The literal meaning of the word universe is ‘all that there is’, so, he reasoned, you can’t have more than one of them. For the purposes of his talk, delivered in Edinburgh in February 1961, he invented the word ‘multiverse’ — by which he meant one of the many worlds. In his own words, he intended it to mean ‘an apparent Universe, a multiplicity of which go to make up the whole… you may live in a Universe full of multiverses, but you may not etymologically live in a Multiverse of ‘universes’.’

Alas for etymology, the term was picked up and used from time to time in exactly the opposite way to the one Nimmo had intended.

The story of Mr Nimmo’s ‘backwards’ definition of multiverse has been picked up from Dr Gribbin’s book, and appears in various parts of the internet. I have been trying to get more detail on this, e.g. from the Interplanetary Society itself, so far without results. For example, I wonder how many people attended Nimmo’s talk, and whether it was published anywhere? We have already seen in this narrative how Schrödinger’s 1952 revelation of his own ‘many worlds’ idea went unnoticed for decades, for example.

Dr Gribbin believes that Moorcock’s multiverse, despite appearing in many bestselling SF and ‘science fantasy’ books, is irrelevant to the scientific discourse, while appearing to suggest that Andy Nimmo’s version somehow seeded its way into the scientific community. I strongly suspect that like Nimmo, he has things the wrong way round.

But part of the purpose of this article is to see if any better evidence might emerge about this process… so let’s see what, if anything, turns up.

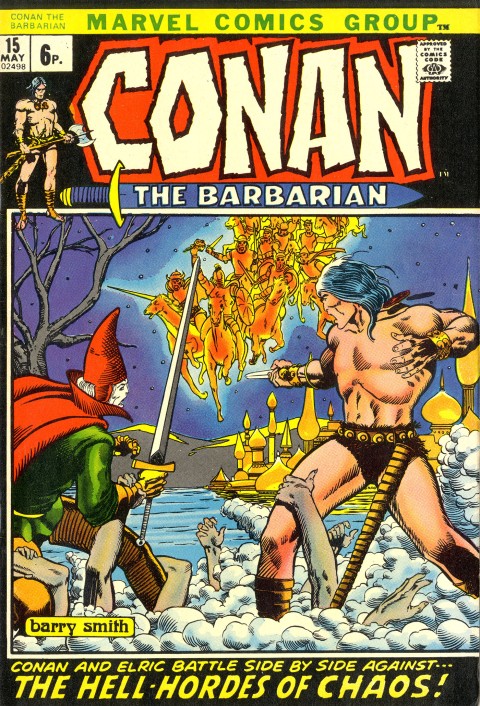

Appendix 5: Moorcock’s Multiverse invades the Marvel Universe

Again, no Time or Space for a major overview of multiverses in the comics (see here as starting point)… but this important point must be made: in 1972 Michael Moorcock’s Multiverse annexed the Marvel comic book universe. This wasn’t a stealth move, comparable to Steve Gerber’s later kidnapping of Howard the Duck and replacing him with a clone. The Multiverse was invited in by Roy Thomas, writer of the Conan comic book, and as these semi-sentient supra-universal entities are wont to do, it waltzed in and gobbled down the lot. It’s just that no-one noticed; as I said before, affairs at multiversal level often don’t impinge on the lives of mortals much. Which means no-one officially told the legal department. Which means that if anyone in Legal noticed, they’d have kept schtum. Because those guys know which way the time-winds blow.

By now there have been so many changes in the ownership of Marvel that any claim from Mike’s side would get so tied up in red tape (and probably a lot of black tape, and also some in nameless eldritch colours) that even a seventh son of a seventh son would have little chance of seeing a dime. And the Multiverse doesn’t care about these trivia. It will just keep turning. So it goes.

Anyway, this is what happened in ’72… Roy Thomas didn’t need to carry out any complex rituals. He simply asked Michael Moorcock and his friend Jim Cawthorn — early artist and co-architect of the Elric mythos—to plot a story for Conan, in which Elric visited the Hyborian Age of Marvel. That was all it took. Any esoteric rune-casting was left up to the pale prince of Melniboné himself.

The very moment that Moorcock’s Multiverse took over the Marvel Universe… Elric appears in its pages for the first time.

Barry Smith (later Windsor-Smith) drew the two-parter. He, being a Brit and a smart cookie, might have got wind of some danger in the air, since he drew Elric in the outlandish gear seen on US paperback covers by Jack Gaughan (vide supra).

This could have been a move to suggest that this wasn’t really Elric at all, seeing as how he’d never actually be seen dead in such an outfit. But informed sources suggest that Mr Smith just made a minor understandable mistake, and no-one has ever doubted that this was a genuine Appearance by the albino Prince of Ruins.

And so, since Marvel at that time only claimed a Marvel universe, Elric’s visit clearly annexed said universe to the greater Multiverse that already constituted the world of Moorcock. This claim, admittedly, hinges on the comic-book Conan and his world being part of the Marvel universe; Red Sonja and King Kull’s 1970s guest-slots alongside Spider-man in Marvel Team-Up seem to have established that nearer the time, and in 2019 Conan himself has finally been fully embraced by the rest of the Marvel comics line…

Q, as they say, ED.

Another day I might also look at how DC dodged this bullet not once but twice; in 1976 their Claw the Unconquered comic (no.7, cover-dated May-June) only shamelessly ripped off the Multiverse notion, without allowing any actual infiltration by the Real Thing.

And in the 1990s, when DC’s Helix imprint published Michael Moorcock’s Multiverse, though it was scripted by Mike, and featured most of his characters, they made sure it didn’t cross over with the DC universe at all. Same with the Elric: Making of a Sorcerer comic that followed. Canny runecasters at DC in those days.

That’s enough of that. Appendix 5 was really just an excuse for some pictures.* You knew that.

Until next time.

© Guy Lawley 2019, 2021

No copyright claimed in images of course, which remain © their respective owners, where applicable.

* it wasn’t.

Pingback: Conan the Barbarian #15 (May, 1972) | Attack of the 50 Year Old Comic Books

Excellent piece there on Conan no.15, and a thorough summing up of the follow-on appaerances by Kulan Gath in various Marvel comics. He went on to become quite the big deal. Fifteen minutes of fame or even more…